Golden Three Ukrainian composers of the 18th century: (from the left)

Maksym Berezovsky (1745-1777), Dmytro Bortnyansky (1751-1825), and Artem Vedel (1767-1808)

The Binghamton Philharmonic's program annotator Ubaldo Valli wrote this reflection on Ukrainian composers.

Cultural identity has been a potent force in human history. Pick any era of history in any area of the world with homo sapiens, and you find examples of cultures wrestling one another and, in the process, finding themselves. Renewed interest in and use of "mother tongues" (for starters: Gaelic, Czech, Bengali, numerous indigenous Native American and African languages); literature exploring legends, myths, and folklore (works by the Norwegian Henrik Ibsen and Argentine Literatura Gauchesca); and visual arts employing motifs from traditional sources (works by the Mexicans Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera and the South African Gerard Sekoto) are just a few examples of assertions of cultural character that were often part of a social and political vanguard.

Music composed by classical composers has also been a powerful tool in establishing and reinforcing cultural identity. Before the Risorgimento united the Italian peninsula as one nation in 1870, Italians shouted “Viva Verdi” after hearing the Chorus of Hebrew Slaves from Giuseppe Verdi’s opera Nabucco (but really were shouting the acronym Victor Emmanuele Re D’Italia in support of the King of Sardinia presiding over a unified Italy). Prior to gaining independence from the Russian Empire in 1917, Finns applauded Jean Sibelius’ tone poem variously entitled Happy Feelings at The Awakening Of Finnish Spring or A Scandinavian Choral March or Impromptu that was composed for a newspaper journalist pension fund benefit concert (knowing full well these monikers concealed the true title suppressed by Russian censors: Finland Awakening or Finlandia).

Music composed by classical composers has also been a powerful tool in establishing and reinforcing cultural identity. Before the Risorgimento united the Italian peninsula as one nation in 1870, Italians shouted “Viva Verdi” after hearing the Chorus of Hebrew Slaves from Giuseppe Verdi’s opera Nabucco (but really were shouting the acronym Victor Emmanuele Re D’Italia in support of the King of Sardinia presiding over a unified Italy). Prior to gaining independence from the Russian Empire in 1917, Finns applauded Jean Sibelius’ tone poem variously entitled Happy Feelings at The Awakening Of Finnish Spring or A Scandinavian Choral March or Impromptu that was composed for a newspaper journalist pension fund benefit concert (knowing full well these monikers concealed the true title suppressed by Russian censors: Finland Awakening or Finlandia).

Ukrainian classical composers also wanted to use their musical heritage in their compositions to establish a cultural identity. However, while their culture has a long and storied history (Kyiv is over 1,500 years old), Ukrainians live at a strategically important geographic crossroads endowed with great natural resources that are coveted by powerful empires. As a result, the nation of Ukraine only achieved lasting independence in 1991 after being ruled for centuries by Russia, the Soviet Union, Poland, the Ottoman Empire, Lithuania, Austria, Hungary, the Mongols... And the occupying empires suppressed Ukrainian culture and institutions (e.g., banning Ukrainian in churches, schools, and theatrical performances or the use of Ukrainian names to christen children) while imposing their own (e.g., making Polish the official state language, pursuing a policy of “Russification”). It was under these conditions that Ukrainian composers tried to find ways to compose that matched their aspirations as Ukrainians.

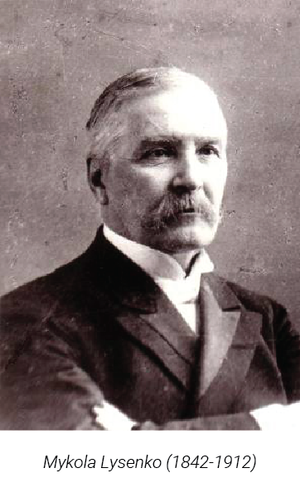

Many Ukrainian composers, such as Maksym Berezovsky (1745-1777), Dmytro Bortnyansky (1751-1825), and Artem Vedel (1767-1808)—known as the Golden Three Ukrainian composers of the 18th century—wrote in a style reflecting the trends of their milieu or left their homeland to pursue lucrative careers in the foreign music centers of their conquerors (Moscow and St. Petersburg being the greatest beneficiaries). However, in the mid-1800’s, Ukrainian composers began to consciously use Ukrainian musical materials to assert their cultural identity. Semen Hulak-Artemovsky (1813-1873) wrote the first Ukrainian language opera, Zaporozhets za Dunayem/A Cossack Beyond the Danube in 1864. Mykola Lysenko (1842-1912) incorporated his studies of Ukrainian folk music and language into his compositions which influenced the music of the next generation of Ukrainian composers (such as Mykola Leontovych (1977-1921—best known for composing Carol of the Bells), Stanyslav Lyudkevych (1870-1979), Alexander Koshetz (1875-1944), and Kyrylo Stetsenko (1882-1922), which dovetailed with the Ukrainian National Revival movement of the late 1800’s.

Many Ukrainian composers, such as Maksym Berezovsky (1745-1777), Dmytro Bortnyansky (1751-1825), and Artem Vedel (1767-1808)—known as the Golden Three Ukrainian composers of the 18th century—wrote in a style reflecting the trends of their milieu or left their homeland to pursue lucrative careers in the foreign music centers of their conquerors (Moscow and St. Petersburg being the greatest beneficiaries). However, in the mid-1800’s, Ukrainian composers began to consciously use Ukrainian musical materials to assert their cultural identity. Semen Hulak-Artemovsky (1813-1873) wrote the first Ukrainian language opera, Zaporozhets za Dunayem/A Cossack Beyond the Danube in 1864. Mykola Lysenko (1842-1912) incorporated his studies of Ukrainian folk music and language into his compositions which influenced the music of the next generation of Ukrainian composers (such as Mykola Leontovych (1977-1921—best known for composing Carol of the Bells), Stanyslav Lyudkevych (1870-1979), Alexander Koshetz (1875-1944), and Kyrylo Stetsenko (1882-1922), which dovetailed with the Ukrainian National Revival movement of the late 1800’s.

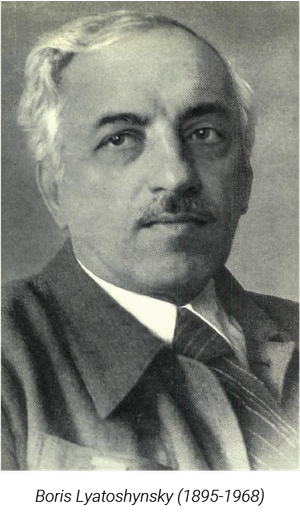

The most influential composer/teacher after Lysenko was Boris Lyatoshynsky (1895-1968). While his early works, written while studying with the Russian-Ukrainian composer Reinhold Glière (1875-1956), reflect his study of Tchaikovsky and Scriabin, Lyatoshynsky was open to the myriad of musical innovations that swept classical music after WW I. This openness, along with an interest in Ukrainian folk music, continued under Soviet rule and informed his teaching of many of the Ukrainian composers of the Soviet and post-Soviet eras such as Valentyn Silvestrov (b. 1937). And, in the post-Soviet era, Ukrainian composers, such as Vevhen Stankovych (b. 1942), Myroslav Skoryk (1938-2020), and Alexander Shchetynsky (b. 1960) have embraced a wide range of styles in their expression of their heritage, an expression that has an international reputation.

Much of the music of these composers is little known outside of Ukraine. The links below give a taste of what we have been missing.

Maksym Berezovsky - Choir Concerto “Do Not Forsake Me.”

Maksym Berezovsky - Symphony in C

Dmytro Bortnyansky - "Sinfonia" (Overture ) to the opera "Il Quinto Fabio"

Artem Vedel - Sacred Concerto No. 9 for Two Choirs

Semen Hulak-Artemovsky – Ukrainian Dances from A Cossack Beyond the Danube

Mykola Lysenko – Taras Bulba Overture

Mykola Leontovych – Prelude for Choir

Boris Lyatoshynsky – Symphony No. 1

Valentyn Silvestrov – Symphony No. 6

Vevhen Stankovych – Ukrainian Poem for Violin and Orchestra

Myroslav Skoryk – Melody

Myroslav Skoryk – Hutsul Triptych

Alexander Shchetynsky – Requiem

Alexander Shchetynsky – Cryptogram

© Ubaldo Valli 2022